The 2022 Iditarod Trail Invitational. Part four of four.

|

| The Kuskokwim River, March 4, 2022 |

The story of my final day on the Iditarod Trail in 2022 has been a difficult one to start. In addition to being my potential last day ever on the Iditarod Trail — at least in the context of this race — this turned out to be one of my favorite days. But if I wrote from a direct perspective, purely about what happened, it would come across as an exhausting, tedious, punishing sort of day — which it was. If I approached the story from the more fluid perspective of my inner world, it would read like a weird fever dream — which it also was. The truth, as usual, is both and also neither, too complex for a tidy narrative. But we keep trying, don’t we, to tell our story? Like anyone attempting to weave tangled threads of experience, I hope to grasp something tangible from the abstraction of memory.

|

| Morning outside Nikolai |

The day started inside the Nikolai checkpoint at the unforgivably early hour of 7 a.m. The checkpoint, located in the village community center, is a large open room with a pool table, a few folding chairs, a bathroom, and a kitchen. When I arrived at 1 a.m., again last in a large conglomeration of cyclists, the only people awake were Troy and a Danish man who I learned was Asbjorn's father. Asbjorn was a skier in the Nome race. The man — who presumably traveled all the way from Denmark to volunteer at this remote checkpoint in rural Alaska — was standing outside and waving his arms when I pulled up to the community center. He had seen from my tracker that I'd spent the last half hour pedaling aimlessly around the village. I found it amusing but endearing that he thought standing in the dark and making this gesture would help me find my way. He directed me inside and offered to cook a hamburger.

“This is only the second hamburger I have ever made,” he said proudly. “I am learning American cuisine. How is it?”

“It’s great,” I chirped, although he could have served a desiccated piece of Spam and I would have eaten it. I was too muddled to be discerning, and my mouth was too raw from several days of frozen nuts to taste much of anything. I felt shattered. Just so tired.

|

| Moody skies over the still well-packed trail outside Nikolai |

I finished my late-night burger and rolled out my sleeping bag on the linoleum floor. The room was lined with wall-to-wall sleeping bags and there wasn't much space left to lie down. I had to squeeze into a spot in the center of the room. Doubtlessly some people had to step over me during the night, but I still slept like a corpse until the final stragglers started moving five hours later. This was my group — the five who shared tent space in Rohn and banded together for the South Fork crossing. Even though I could barely sit up, I felt compelled to follow them.

When I say I could barely sit up, I’m not exaggerating. I must have crashed my bike at least a dozen times the previous day. My pre-dawn body slam on hard ice had limited the mobility in my left hip, but this limp was just the beginning. My entire body was a knot of pain. I was lucky to have cleared the moguls without breaking any bones, but every joint creaked and groaned. My muscles felt tenderized. My bruised skin was throbbing. Every limb was stiff. My older injuries — the back pain and broken toe — were still there, but so muffled by the screaming from everything else that they hardly registered.

When I was still weirdly contorted in my sleeping bag on the floor, Becca walked by and asked if I was planning to leave soon.

“I need to summon the will to live,” I croaked. I wasn’t exaggerating about this, either. If I had two buttons and one said “ride to McGrath feeling the way you do” and the other said “die painlessly,” it would have been a genuine toss-up.

The official checkpoint volunteer, George, was sitting at the kitchen counter and barking at his phone. Apparently, Lindsay, the 70-something Canadian cyclist, was injured near the Farewell Lakes and had requested a rescue. A volunteer from Rohn had already tried to get through without success — the bumps were too much for his machine.

“It’s too windy for anyone to fly,” George said into the phone. “What does he expect us to do?”

|

The Kuskokwim River as seen from the air

|

Indeed, despite the minimal windows in the room, I could hear an ominous knocking against the walls. The wind had returned and it was unlikely to be the tailwind we’d enjoyed the previous day. The trail beyond Nikolai went generally west but also occasionally turned south along the meandering Kuskokwim River. As I creaked to a standing position, I visualized the route map superimposed over what I still believed to be the wind direction — the previous day’s 25 mph southwest winds. A destabilizing crosswind and drifted trails seemed all but certain. This would turn out to be an optimistic assessment because the wind had shifted to the south.

Beat and I joke about how people always overestimate wind speed. Winds are always “At least 50 mph, probably gusting to 80!” I do this too, even though I know that if the wind was actually blowing 80 mph, my body would be splayed on the ground and I would be forced to crawl if I wanted to move at all. So, for this report, I checked the weather record for March 4 at the Nikolai airport — keeping in mind that winds are often higher on the river. When I left town at 8:10 a.m., the wind was blowing SSW at 16 mph, gusting to 28. This would increase throughout the day with a continuous wind speed of 26 mph and gusts as high as 53 mph. Trust me when I say this is a lot of wind.

While packing up to head out, a gust caught my red bivy bundle and blew it a few hundred yards down the snow-packed street. I had to sprint after my survival gear, stumbling and groaning in pain. For two miles the trail follows a village road through the woods before dipping onto the frozen Kuskokwim River. I stopped a number of times for any excuse I could imagine just to avoid the inevitable. Even with the relative protection of the woods, crosswinds knocked me to and fro. My legs throbbed. I was miserable.

|

| Morning light on the Kuskokwim River |

Then I thought of a mantra that my friend Jorge mentioned after his 2018 walk to Nome. It sounds bleak but it works for me — an unapologetic pessimist whose mental scaffolding is prone to collapse before the game is over. The mantra is, “This is never going to end.” I repeat it to myself when I’m frustrated. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel. There’s no end to the discomfort. And if there’s no end, then how do I learn to live here?

Somehow this worked. My focus shifted from misery to renewed determination to embrace the difficulty and ignore the pain. I dropped onto the river, buffeted by a fearsome crosswind. Several inches of spindrift coated the trail. Finding the rideable line wasn’t trivial. Beneath the windblown powder was an intermittent mix of packed snow and whipped-up, mashed potato snow. The mashed potato snow was too soft to support my weight. But the packed snow surface remained hidden from view. Keeping the wheels turning became a kind of Zen meditation, an indescribable sense of knowing the unknowable, of finding the way by intuition alone.

|

| Drifted snow over the trail |

It sounds hokey now, but I was mesmerized by the effort. For timeless miles I remained wholly absorbed in the next pedal stroke, the next shimmy of the handlebars, always holding my invisible line and never wavering even as the south wind continued to rattle me violently.

Bobbette and Becca were about a quarter-mile behind. Snow continued to blow across the trail, erasing my tracks. Although riders had been through just a few hours before, there was no evidence of their passing, either. This is something I respect about winter trails — they are always changing. In this way, "ghost trails" are living works of art: an embodiment of the impermanence in all things.

Each moment that my mind, body, and soul were wholly absorbed in drawing a perfect line in the snow, that’s all it was — a moment. Wheels turned, spindrift filled in my tracks, and it was as though I was never there. Can you understand the freedom therein? It was exhilarating. If I exist in a world without end but also without beginning, then each moment is everything. There can be no past filled with pain, no future weighted with worry. And each moment — the snow, the moody sky, the distant mountains stretched along the horizon — was indescribably beautiful.

|

| Pushing when the drifted snow was too difficult to ride |

My mind did occasionally wander. My moving meditation was interrupted by the most random memories: people I hadn’t thought about in years, insignificant snippets of the past. Memory can be so fickle. I suppose this is another beautiful embodiment of impermanence: the vignettes of life that we carry in our subconscious, for reasons we don’t even understand.

Though bewildering at times, it was interesting to wend through the lesser-traveled corridors of my mind. Some memories bordered on hallucinations, closer to a sleeping dream than a daydream. For long minutes, I’d be wholly immersed in the neon lights of State Street in Salt Lake City, a teenager in a car surrounded by nearly forgotten yet vivid sounds and smells — the lime yogurt that fermented and then exploded in the trunk of my friend's Chevy Cavalier, Queens of the Stone Age playing on a garbled FM radio station.

It was so real. Then, as though being pulled out from underwater, I’d snap back to howling wind and an invisible line in the snow. These fluctuations between past and present became unnerving, enough so that I forced myself back to a more normal state of mind — one that, unfortunately, was more attuned to pain and boredom.

|

| Breaking my bike down to carry it up this short but steep embankment |

The trail also became more dynamic, with bumpy shortcuts through the forest, stretches across swamps where the loose snow was too deep to ride with or without Zen techniques, and punchy climbs and descents on and off the river. One embankment was only about as high as my head, but the climb was nearly vertical, slicked with ice, and impossible. I tried several methods of hoisting my bike to the top before I finally relented to removing the bags. I hooked the frame to my backpack and climbed the embankment, kicking tiny steps into the ice and using exposed roots as handholds. I returned two more times for the bags. Though successful, the experience rattled me a little bit. I suddenly felt vulnerable. What if I came to an embankment that I simply couldn’t climb up? It wouldn’t take much to break me, and this wind-blasted wilderness isn’t kind to broken people.

The trail cut through the woods and dropped back onto the river, this time heading due south. The wind, doubtlessly gusting to 50 mph, became an invisible but impenetrable wall. I could no longer ride forward. Genuinely, I could not. I felt so exposed. It wasn’t that cold — certainly, it wasn’t 45 below like 2020 — and yet I felt the same sort of unease, a realization that my human body was exceptionally fragile.

This realization is one of the reasons I don’t think I will return to the Iditarod Trail, at least not in this context — as an endurance racer, pressed against my soft human limits.

|

| The isolation I can feel out there is difficult to depict |

Earlier this year, when I admitted to friends that I did not want to return for the 2022 race, I heard similar assurances: “It’s okay. You’ve had a tough year. You have nothing to prove.” But I never had anything to prove. It was always hubris to believe I could “conquer” anything, that I could take my weak human body on a difficult journey and somehow this would solidify my inner strength. This trail has crushed my inner strength again and again — in good ways, memorable ways, ways that have made me a more empathetic, adaptable, and mindful person (cracks are where the light gets in, after all.) But as the years have rattled my physical and mental health, I better understand how I can be weakened by these endeavors. Some cracks don’t heal. I can’t risk shattering completely.

For now, I was fearful of shattering but also stuck. McGrath was still 20 miles away and I was going to have to power myself through this wind wall no matter what. (As the Lindsay drama demonstrated, help is not guaranteed even if I was in real distress, which of course I was not. Lindsay was eventually able to mobilize a ground rescue from two Nikolai residents on more powerful snowmachines, but even that was a complicated undertaking.)

|

| Fighting for the perfect line |

Writing about it now, all of the fear I was feeling seems overwrought. But it was genuine, because most of it was rooted in the well of the exhaustion and pain that I had managed to cover up for much of the day. When I looked up to face the wind, the difficulty seemed overwhelming. But as soon as I stopped struggling in the pedals and relented to walking my bike, I settled back into steady motion.

There was one more difficult obstacle to face: a steep climb over a bluff that shortcuts an oxbow bend in the river. For miles, I couldn’t shake my stress about this upcoming climb. I know it sounds silly, but I was fearful that I wouldn’t be strong enough, that I simply wouldn’t make it. I knew a few snowmachiners in the Iron Dog Trail Class cut a trail that followed the river around the oxbow, but this prospect was also ridiculous. It added at least five miles, and half of that was due south into a headwind that was arguably even more unmanageable than the steepest grade possible. As it turned out, the wind had entirely erased the river trail, so the only option was the shortcut. I was physically shaking. As nervous as I was at the time, I was also rolling my proverbial eyes at myself. “How far I’ve fallen. Once I found the courage to venture into the Alaska wilderness when I knew effectively knew nothing. Now I know so much and I can’t even face a hill I’ve climbed before.”

The hill, of course, wasn’t that bad, except for a large birch tree had fallen over the hillside and was blocking the entire trail. It wasn’t all that trivial to break a footpath through the deep snow around the tangle of branches, but it wasn’t that bad. I wasn’t about to fall backward like I nearly had on the Post River Glacier, and I didn’t have to break down my bike and carry it up in pieces, so it wasn’t that bad.

|

| Ripples in the snow |

And then I dropped back onto the river, where the trail had filled with drifting snow. The spindrift had a beautiful, rippled pattern, like fine grains of sand in a white desert. A fierce crosswind continued driving sand — I mean snow — over the surface. The afternoon sun illuminated streams of spindrift, which resembled fingers of light. The way these fingers reached out from the woods evoked a haunting feeling, as though the wind was alive. And although this wind spirit didn’t feel evil, the sensation of being haunted was visceral enough that I decided it was again time to get out of my head. Earlier I’d turned off an audiobook to concentrate on the sinister hill, so I switched my device to a music playlist. As though the spirit of the wind was speaking directly to me, what should be the first song to come up? “Addict with a Pen.”

These are just pop songs, I know, and it’s silly that I keep bringing them up, but the way they give voice to my moods is a crucial part of the experience. This song by Twenty One Pilots was the one that happened to come on during my last endurance race in September, the Utah Mixed Epic, in a pivotal moment when I lost myself to grief and collapsed in a nondescript high-desert valley in Central Utah. I curled around my knees on the rocky ground and cried excruciating yet liberating tears. As the song ended, I struck up a conversation with my father. It felt so real, and it lent me a few moments of immeasurable peace. For the same song to play now, pulsing with the rhythm of the wind and blowing sand — I mean snow — was surreal. It swept me back to that rust-colored hillside in Utah, the wisps of clouds in a cerulean sky. I’d returned to the desert, and I was again swept into all of the emotions all at once.

But I try my best and all that I can

To hold tightly onto what's left in my hand

But no matter how, how tightly I will strain

The sand will slow me down and the water will drain

|

| Trying to capture the dynamic dance of wind and sky |

My eyes blurred with tears, and then the sky began to dance. Amid the blowing snow and jet stream of clouds, the sun’s rays shimmered and swayed. The scene was indescribably beautiful. I took several photos that do it no justice, but my grief- and joy-stricken mind perceived this place as otherworldly, magical, as dynamic as a galaxy compressed in a pinpoint. In the physical world, I was stumbling through ankle-deep spindrift, leaning into the lee side of my bike as the crosswind froze the tears on my cheeks … but in my mind, it was one of the most phenomenal moments of my life.

|

| No, I couldn't really capture it. |

My reverie broke when the trail ascended another near-vertical embankment and cut through the woods. The roar of the wind gave way to a muffled whistle through tree branches, which sounded comparatively silent. A sign said McGrath was 10 miles away. Pain and fatigue returned. I crossed swamps and battled headwinds. The trail again dropped onto the Kuskokwim River, wending briefly north and then due south.

It was late evening now, with soft pink light stretched across the horizon. The wind was as strong as it had ever been. When I hit the invisible wall on the southward bend, I threw a foot down and looked up. I was just two miles from the end. I could see the McGrath airport. But I couldn’t move.

|

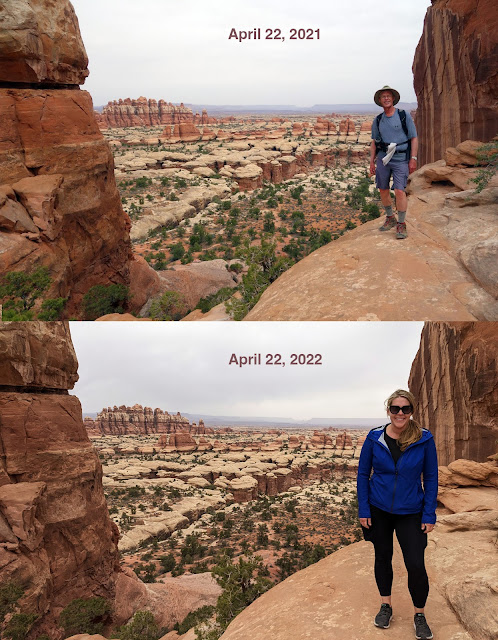

| Standing at the start of the Iditarod Trail Invitational with my first fat bike, "Pugsley," in February 2008. I like to look at this photo and ponder the ways in which I've come full circle. |

Fourteen years ago, I met a similar wind on the Kuskokwim River. Spindrift masked the trail entirely. At times I couldn’t even tell whether I was still going the right way, but back then I was naive enough to not be frightened because I had a plan. My plan if I lost the trail was to hike in a direct line guided by my GPS — this was back when I believed such a ridiculous thing to be possible. I somehow held the correct path and climbed off the river — my perceived final challenge — only to be blown into a snowbank by an errant gust. My bike landed on top of me, effectively pinning me in a hole. I didn’t have the energy to lift myself then, either. I remember how that surprise setback evoked all of the emotions, everything all at once, and I laughed and cried before summoning an empowering burst of strength. Now it seems so long ago, and also just a blip in time.

What have I learned after all these years? How does that lyric go? “I was so much older then; I’m younger than that now.” My dad loved The Byrds.

Often I think middle-age is similar to adolescence. Your hormones are changing, your worldview is shifting, and the full scope of adulthood no longer makes sense. You don’t have your path figured out the way you once did, because life isn’t a linear journey. Life is long, and the more you live, the more you’ll change. Life is loss, and the more you live, the more you’ll lose. Life is exploration, only to realize that the more you learn, the less you know. Life is hard, but not because you decide to pursue hard things. It’s hard for reasons you’ll never control, and you have to learn to live with that, too.

And I suppose that this — standing frozen river with a 50 mph wind blowing in my face — is one of life’s absurd situations that ultimately means something. Because I chose it, and because I love it, in spite of its absurdity. Because it’s beautiful and rewarding, in spite of also being tedious and pointless. Because I watched the sky dance in a moment of clarity that I will cherish always, even as my path takes me far away from here. The Iditarod Trail is a microcosm of life, which is why we keep coming back. I told myself that this was the last time I would come back — I continue to tell myself this — but I can’t know what the future holds.

|

| Final selfie, one mile from McGrath |

For a few seconds, the wind quieted. I took advantage of the lull to launch my bike forward. Even as gusts picked up, I continued summoning all the energy needed to keep the pedals turning. Time seemed to warp — it took nearly an hour to pedal that final two miles. A local drove by on a snowmachine and congratulated me. As I neared the riverbank, the final home-free, I upheld a long-standing tradition to let the music playlist decide the theme song for this adventure. So I hit next and heard the intro to “Go Solo” by Tom Rosenthal.

I promise: I am not making up any of these random music selections. Of course, I only write about the ones that were implausibly relevant, but this adventure couldn’t have finished on a better note:

Our love is a river long,

The best right in a million wrongs.

I know I'm coming back to you.

And I'm happy,

nothing's going to stop me

I'm making my way home,

I'm making my way.

|

| Arriving at the McGrath finish with my current fat bike, "Erik," on March 4, 2022. |

It took longer than the song’s three-or-so minutes to pedal a mile, so I continued hitting repeat until I rolled up to the lodge. My friend from Boulder who was volunteering at the checkpoint, Cheryl, was standing outside waiting for me, as were two ladies who finished earlier — Beth and Janice.

Janice asked what finish this was for me.

“Number six,” I replied, and then clarified. “Three on a bike, three on foot, but once on the bike I was on my way to Nome, so that didn’t count, and once on foot I intended to go to Nome, so that was a DNF.”

Janice mercifully cut me off. “Six,” she said. “Nice work.”

|

| Faye Norby is exhausted after finishing as the first woman on foot in 6 days, 13 hours |

As for the 2022 stats, Amber won the women’s bike race in 4 days 11 hours, Beth was second in 4 days 18 hours, Janice finished in 4 days 21 hours, I was fourth in 5 days 4 hours, and Bobbette and Becca rolled in an hour later in 5 days 5 hours. Jennifer Hanson was the seventh finisher in 6 days, 1 hour.

None of us went onto Nome — in a field of 30 Nome hopefuls, sadly none were women this year. But I am heartened to see how women’s participation in this sport has grown over the years. In addition to the seven cyclists, there were three women on foot and two on skis. In 2008 it was just me and the co-race director, Kathi Merchant, and two women on foot, Loreen Hewitt and Anne Ver Hoef.

|

| Beat arrived in McGrath early in the morning on March 6 and left 12 hours later. He won the race to Nome and received a free entry as a prize, so of course he plans to return in 2023. |

Despite all of the difficulties, I had an incredible experience on the Iditarod Trail this year and am glad I made the decision to ride to McGrath. I nearly left it at DNF’ing the walk to Nome in 2020, and am grateful that wasn’t the final chapter. While I’m not certain this is the final chapter, I am content with being “retired” from Iditarod racing for the time being. It’s an opportunity to reflect, refocus, and imagine where I might be 14 years from now — should I be so lucky to still be writing my own story.